Chapter 5: The Rise of Rescuer Stories

Trauma Doesn't Teach

These stories of rescuers’ bravery and altruism often serve as an effective gateway for students to identify not just with people from the Holocaust, but also with their own present-day role when confronted with the choice between good and evil and the consequences each one brings. The Holocaust is one of history’s clearest examples for students to study “the full continuum of individual behavior, from ultimate evil to ultimate good” (Lindquist, 2011a) and hence the moral implications of their decisions. Under the pressure of war and surrounded by death, people decided which side of history they were on and moral courage either emerged or was suppressed. In these stories, students can reflect on the roots of their own decisions and how they could contribute moral values in their own community. Perhaps more importantly to young people, knowledge of the rescuers’ bravery in the context of the war – “when light pierced the darkness,” to pull from Tec’s book title - gives students hope when so much around them today insists there is none. Ivy Schamis, the Holocaust education teacher from Marjory Stoneman Douglas high school in Parkland, Florida, said (Bairnsfather et al., 2021):

“I never would teach a class without giving hope to what happened with people that were maybe not-so-famous rescuers, like Leopold Socha who helped people in the sewers of Lwow (Poland), or (Aristides de Sousa) Mendes who helped write visas for people in Portugal. So I think that the hope is there and I believe that’s also what gives students the hope in what’s happening in today’s world.”

Additionally, rescuer stories provide a unique perspective to learn about the Holocaust without making the student confront traumatic images or stories when they are not emotionally prepared. Through the lens of the Righteous Gentile, they can safely become exposed to the atrocities and evil while adopting a feeling of protection from the rescuer. Shulamit Imber was Yad Vashem’s first Director of Education in the 1970s when there were no Holocaust education programs. She began from scratch with groups of experts to assemble programs that have since been used in classrooms around the world. Over the years she has learned (Imber & Jacobs, 2021):

“Trauma doesn’t have a meaning. Teaching death doesn’t give meaning. Don’t give them numbers or shock, give them the human story about what was lost. Teach them empathy through learning what life was before and what was lost. Teach about the trauma without traumatizing. Bring the students safely in without trauma. Teach them survivor and rescuer stories. The survivors are our moral authority, they give us a backbone. Safely in, safely out.”

Rescuers themselves became advocates of teaching young people their stories as examples of humanity. Jan Karski of the Polish underground became a professor at Georgetown University. In his 1988 Christian Rescuers Project testimony, he says:

“What must be emphasized, and many Jews do not do it enough, particularly those who teach Holocaust, particular to the children, we must be very careful if the teacher is not qualified, he or she will run a risk corrupting the young minds. First, that such things were possible, such horrors happened. Corrupting the minds of young people will lose faith in humanity, particularly the Jewish children. ‘Everybody hated us. Everybody is against us, so I must be only for myself, I must mistrust everybody because I am Jewish.’ This is unhealthy, we don’t want them to lose faith in humanity.

To speak about Holocaust, a good teacher, particularly for the children, he should emphasize ‘Don’t lose faith in humanity.’ With the governments, be careful. The governments have no souls, they have only interests in mind. But with individuals…not all humanity abandoned the Jews. There must have been hundreds upon hundreds of thousands of individuals to make possible over half a million Jews survive. Children should be taught about, otherwise if we are careless we may corrupt their minds.”

A Society Ready for Change

Robert Putnam explains in his 2020 book “The Upswing” that our current American society has devolved into an individualistic one where everyone from big business to our neighbors are putting themselves first. His extensive research shows economic, political, societal, and cultural patterns that we are deep into a selfishly driven, divided era similar to the Gilded Age of the 1870s and 1890s when, “Inequality, political polarization, social dislocation, and cultural narcissism prevailed — all accompanied, as they are now, by unprecedented technological advances, prosperity, and material well-being.” Progressives of the early 1900s changed that trajectory to a community-driven trend when “equality, inclusion, comity, connection, and altruism” were emphasized. The political divide was narrower, there was more economic opportunity for all classes.

To climb out of our current place in the “I-We-I” social curve, Putnam postulates that energetic, young Americans must find their shared core values and work in a bipartisan, grassroots effort to make the change while they, in turn, become leaders with strong morals. They can begin to sculpt the future social, economic, and political landscape as they did over 100 years ago. With a background in lessons from the Holocaust, the resiliency of the survivors, and altruism of the rescuers, these youths can be inspired to redirect our society back in a moral direction.

Leaders in Holocaust Education

Fortunately, there are education leaders with this kind of foresight to not only take the messages from the Holocaust to their students, but also to take them to new levels that perfectly align with what our society needs in order to reclaim moral values and tolerance. Today’s model of Holocaust education is not the same footnote of gruesome, historical statistics from a few decades ago. It has evolved into a multi-discipline approach bringing together history, global studies, psychology, civics, sociology, and others.

While some states have mandates on Holocaust education, such as Florida, others, such as Pennsylvania, only have recommendations. However, neither path guarantees that a school district will be funded, that a tenured social studies teacher will change their curriculum, or that a new teacher with innovative pedagogical ideas will be supported by administrators. Florida has had a Holocaust education mandate since 1994, but it came without supplemental support, funding, or buy-in from school districts. Only in 2012 did Schamis’ school obtain the support of administrators and the resources to begin a holistic Holocaust education class. Right away, students were signing up and telling their friends. It pulled in students throughout the high school’s diverse student body and quickly grew to eight fulltime classes per year. The students were engaged in the material that included other genocides, social justice, and examinations of news around the world. Even if they couldn’t relate to a genocide in Rwanda, they could still learn to have empathy for others. Schamis says (Bairnsfather et al., 2021):

“The key in all of the lessons we taught was how to distinguish yourself as an upstander. Because saying nothing and indifference is really the opposite of love, not hate. It’s really being indifferent, and how you can be an upstander.”

The LIGHT Education Initiative

For the past four years, the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh has presented the Holocaust Educator of the Year award to a local teacher who “encourages critical thought and personal growth through lessons of the Holocaust” (Haberman & Bernstein, 2021). In 2018 that award was given to Shaler Area High School teacher, Nick Haberman. He began teaching history and social studies in 2006. He inherited the existing Holocaust curriculum “as a non-Jewish kid from Etna with no Jewish friends and no experience studying the Holocaust and nobody in my family having lived through it.”

Nick Haberman of Shaler Area High School and Holocaust Educator of the Year (photo: Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh YouTube)

Undeterred, he was encouraged to seek out the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh for educational resources, and most importantly, to bring a Holocaust survivor into his class. After a few phone calls, he made a connection that became a catalyst for his life as a teacher: Jack Sittsamer.

Sittsamer was born in Poland in 1924 to a large, Orthodox Jew family in a town with mostly Catholics. When the Germans invaded, he watched in horror as they burned synagogues and round up other Jews and murdered them in a slaughterhouse. He and his family were forced to march to an airport hangar, herded by Nazis on motorcycles and German Shephard dogs. His father, who was injured fighting in World War I, could not keep up and was shot. The teenager was separated from his family and never saw them again after they were ordered to board other trains. Because of his youth and strength, he was selected to be a laborer at various concentration camps, enduring transits in boxcars to Auschwitz and Mauthausen, living behind electrified fences and barbed wire in a striped uniform under the eye of guarded watch towers. He was forced to perform heavy labor every day on 12-hour shifts, building tunnels and working through typhoid fever, whittling down to 80 pounds of “skin and bone.” After the liberation by the U.S. Army at the Gusen II concentration camp near Mauthausen on May 5, 1945, he learned that he was the only survivor from his family (Sittsamer, 1989).

Haberman vividly recounts the first time talking to Sittsamer on the phone, arranging the speaking engagement for his class. He naively expected that Sittsamer would only talk to one class, but the 82-year-old took charge by saying:

“Give me all the kids. The whole school. I’ll talk to all of them. As many as you can get. That’s how many I’ll talk to.”

Jack Sittsamer, 2007 (photo Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Darrell Sapp)

Sittsamer told his Holocaust story for 90-minutes in front of hundreds of captivated ninth graders and teachers. At the end of his presentation, Haberman says you could hear a pin drop. Teachers wept, students rushed the stage to shake Sittsamer’s hand, give him a hug, and take selfies. The line went around the stage and Haberman was left stunned at the impact that one survivor could have.

On the drive home, Sittsamer was straight up to Haberman. He explained with no emotion (Haberman & Bernstein, 2021):

“You know, I’m going to die soon and when I do it’s up to you to tell my story…I’m going to be gone and all the educators are going to be responsible for carrying on the stories of survivors, so you’ve got to carry on my story.”

Sittsamer passed away less than two years later, but his lesson stayed with Haberman. The epiphany left him realizing that teachers have a great responsibility to teach the Holocaust for the long haul and it would require a new model. It would need to be sustainable and draw students in so their learning would not end at the door or when submitting a “disposable” assignment. It needed to seek change in the students and their community.

Over the years teaching the Holocaust, Haberman surrounded himself with experts rather than reinvent what they had already been done so well. He became a teaching Fellow at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum and attended the rigorous Jewish Foundation for the Righteous teacher training at Columbia University, obtaining the certificate of Master Teacher of the Holocaust. These experiences fortified his confidence to developing a holistic model of teaching the Holocaust. Students need to connect to something so long ago by drawing in how it relates with contemporary issues such as racism, antisemitism, gender inequality, identity-based discrimination, genocide awareness, immigration, and other social problems. He notes that often teachers feel they need to dance around sensitive topics, but in reality the students are already talking about them. They need a trusted, safe place to ask questions and find facts. Rather than teach in a silo of history or social studies, he connects the students’ learning with teachers in other subjects such as art, writing, multimedia, and political science. In his classroom, he was seeing the progress not just in students’ learning, but they were having fun. He designed the class so that it became student-led and they decided what was important to them. They were connecting lessons of the Holocaust with topics that concerned them today and learned step-by-step how they could influence change.

He also believes that the current education model has successfully taught students problem solving skills from STEM (science, technology, engineering, math), but to continue their success as citizens in their community, they also need to connect that learning with the humanities. The wave of STEM success should also be applied to human-based problems that they face every day, whether at home, in their community, in school, or in events around the world.

When Haberman won the Holocaust Educator of the Year in 2018, its monetary award gave him the opportunity to take the model of what he had been doing in his classroom and share it with other teachers and school districts. He wanted to use the award to create something that could last the long-term rather than be a one-time investment. Like Sittsamer, he felt an obligation to ensure his stories and methods for teaching would be around long after he was gone. The award acted as seed money to help him launch a non-profit organization called the LIGHT Education Initiative (Leadership through Innovation in Genocide and Human rights Teaching).

The program seeks to solve a common problem teachers face of not having the resources to embed a sustainable, holistic program about the Holocaust or opportunities to have their students apply what they are learning to problems they see in their own communities. Its essence is to inspire, prepare, and empower students. They are given the structure to encourage project-based learning. By taking previously learned STEM skills, students can apply them to human-based problems using new skills from the humanities to solve problems in their community. Students learn leadership, networking, team work, problem solving, communication, goal setting, and most importantly - empathy. Using LIGHT as an educational vessel, they learn the basics, from improving their writing skills to promoting an event to recording a round table discussion for Black History Month. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Haberman’s students wanted to have the Pennsylvania state legislature acknowledge April as being Genocide Awareness Month. They worked with both a local conservative Republican politician and a liberal Democratic politician to create bipartisan language supporting their proposal. Then the students met virtually online with state legislators and provided a convincing argument to pass it with bipartisan agreement. For perhaps the first time in their young lives, they realized their actions could help others. With the opportunities from LIGHT they walk away from the class with skills to carry forward the rest of their lives.

Haberman knows from his years of experience that school districts need to have the incentive to support new programs. LIGHT has made every effort to remove the financial barrier by providing grant money for schools to begin their own program. For the teachers and administrators, LIGHT becomes a free, open-source teaching infrastructure that they can plug into their own curriculum and design as they want. They can make it as big or as small as necessary, always knowing that it is a dynamic process with room to grow.

Students learn through their Holocaust education studies about accepting people from different cultures and backgrounds. It is important to students to be exposed to these cultures even within their own city. One of LIGHT’s programs is to provide both teachers and students local, cultural experiences beyond the typical museum experience. In the Pittsburgh area, LIGHT partners with small institutions that cater to community building and bridging art with social justice. At places like the Maxo Vanka murals in Millvale and the Carrie Furnace in Homestead, students can learn about the city’s immigrant experience, which ties in with human rights, diversity, and acceptance. Future plans are to coordinate with the August Wilson Center and Roberto Clemente Museum. At a recent event called “Bad Activist,” students from different school LIGHT programs got together to hear a local activist encourage how to influence change, then had lunch at a local restaurant, hung out at a library making buttons and learned to record videos of the group’s experience. It was “simple, fun stuff,” but everyone was “glowing” after with their newfound companionship and friendships built on community-driven interests. Again, Haberman’s foresight removes the financial barrier for school districts to support this kind of experience. LIGHT has the funding and coordination in place to fully subsidize and coordinate a day’s field trip: from the bus, to the tour, to a prearranged lunch. It even includes paying for a substitute teacher.

CHUTZ-POW! Superheroes of the Holocaust

The Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh has been a touchstone for the Jewish and Holocaust educational community for forty years. Their mission is to connect “the horrors of the Holocaust and antisemitism with injustices of today. Through education, the Holocaust Center seeks to address these injustices and empower individuals to build a more civil and humane society.”

CHUTZ-POW! Project Coordinator, Marcel Walker (photo Pittsburgh City Paper, Jared Wickerham)

Four of the CHUTZ-POW! comic book series

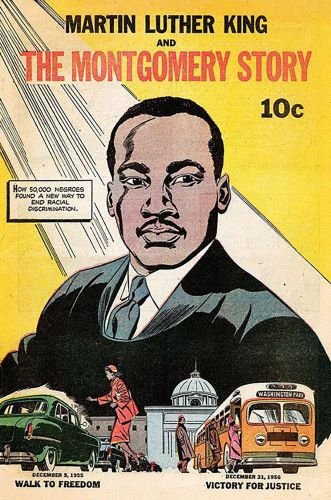

A pillar of the Holocaust Center’s education program is their self-published comic book series called CHUTZ-POW! Superheroes of the Holocaust. Its project coordinator, Marcel Walker, has been a life-long reader of comic books and explains that they were historically used to reach readers of all ages, not just children. The Golden Age of comics was in the 1930s and 40s, which coincided with World War II. Some of the original creators of comic books were Jewish and during the war, interest in comic books soared. They became the perfect medium for providing “cheap, portable, and inspirational, patriotic stories of good triumphing over evil.” They sold by the millions and were sent in care packages to soldiers overseas (Walker, 2021). Captain America was originally created to support the war effort. Its first issue in March 1941 showed the masked American hero in his bright red, white, and blue uniform and shield socking Hitler to the ground while dodging Nazi bullets. It cost only 10 cents.

Comic books were considered a creative medium on par with movies in their diverse subject matter and more mature, real-world themes. Walker points out that two of the most influential and important comic books ever published were about social justice. In 1957 the comic book, “Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story,” was published and became a rallying cry and educational device for civil rights activists. It told the story of the Montgomery Bus Boycott and Rosa Parks, and a young pastor leading the protest named Martin Luther King, Jr.. The book went even further by providing guidance on how the reader and other activists could use nonviolent protests for social change. In the U.S., it influenced John Lewis and a whole generation of young, civil rights activists, as well as other events around the world such as anti-apartheid protests in South Africa (Klein, 2020). The other important comic book that Walker identifies was Art Spiegelman’s series, “Maus,” the only comic or graphic novel to win a Pulitzer. The series was created from 1980 to 1991 and was published as two complete book editions in 1992, when it won the Pulitzer. The first book told the story of Spiegelman’s father as a Polish Jew before the war and when the German’s first occupied Poland. The second book was the story of his struggle to survive at Auschwitz and Dachau, the camp’s liberation, and his life after (Meir, 2019). Spiegelman’s ability to weave an engaging, visual narrative of the Holocaust’s horrific truths with the human element of his father’s experience, foibles, and the love story with his first wife who was also at Auschwitz, make it a frequent educational tool used alongside “The Diary of Anne Frank” and Ellie Wiesel’s “Night.”

“Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story” comic book from 1957 that helped to lead the civil rights movement

Art Spiegelman’s “Maus” series that won the Pulitzer in 1992

Walker explains that the tie between superheroes and the Holocaust is closer than one might think because superheroes often came from traumatic experiences. He is particular fond of Superman, who as a boy was sent away from his home world of Krypton by his parents moments before the planet was destroyed. His space capsule landed on Earth and he was all alone to find his own path even as he was taken in by the meaningful Kent family. Throughout the comic series, Superman must revisit and process this childhood trauma. The parallels to what Holocaust survivors went through is important because the young reader’s relationship to the superhero teaches them empathy, which they learn to apply elsewhere:

“Comics, as literature, can help us process trauma and help us develop empathy for others’ experiences.”

Additionally, comic books are an effective education tool when they make the subject matter more interesting and hold a young person’s attention far longer than typical schoolbooks filled cover-to-cover with only words:

“It makes it educational and not boring. I was always bored by typical text books.”

Given the long history of comic books as a medium for telling the story of difficult, but important, topics, it was the obvious choice when the Holocaust Center decided in 2013 to create a series of instructional narratives based on Holocaust survivors. Their goal was for the series to be scholastic as well as read by a general audience. The series would also change the perception that Holocaust survivors were victims by more accurately framing them as resilient superheroes. Similar to the characters in mainstream comics, the CHUTZ-POW! stories take the reader through the subject’s upbringing, their personal experience of the Holocaust, their fight to survive, and reflection later in life. When Walker and his team are developing the stories, they work closely with the survivor to portray their memories on paper. Their artistic freedom brings the scenes from 80 years ago back to life. They can recreate pictures of what the survivor experienced in the concentration camps or hiding in the forests. They also rely on detailed historical research to make the stories as accurate as possible, from the Jeeps used by the U.S. Army to the faces of supporting characters. For many readers, this would be the only visual of what the survivor experienced since there were no cameras or videos to capture their daily life (Walker, 2021).

One of the first subjects of Issue #1 was Pittsburgh Holocaust survivor, Fritz Ottenheimer. Before he passed away in 2017, Ottenheimer frequently spoke to students about growing up in Germany in the late 1930s as the Nazi propaganda machine changed his family’s life forever. His father’s shop was shut down by the Nazis as loudspeakers blared about not supporting Jewish businesses. Defiant, his father created a display in the store window of his medals from World War I fighting for Germany. The machine, however, was persistent and soaked passive communities with its messages of divisiveness. Even his regular non-Jewish playmates were being sent to Nazi Youth meetings and taught how to rethink their friendships. Jews from other parts of Germany came to his father for help as they tried to flee to nearby Switzerland. Luckily, his family was able to leave Germany in 1939, but he returned in 1945 as an enlisted U.S. Army serviceman to help the Allies and “de-Nazify” his homeland (Wise, Moeller, Wachter, Walker & Zingarelli, 2014).

Seventy years later, Ottenheimer was holding a copy of the comic book in his hands, fresh off the press, and flipping through his story recreated in panels of detailed black and white imagery: his father’s shop with a window displaying his medals from World War I; playing ball with his friends in the Nazi Youth; the smoke and debris from Kristallnacht; arriving in America and seeing the Statue of Liberty; returning to Germany near the end of the war as an enlisted serviceman in the U.S. Army; surveying the damage and atrocities of his former home and wondering how 65 million Germans could have become bystanders. Ottenheimer smiled with pride at the book and read out loud the final sentence of his story that signifies the importance his parents made on him:

“When you’re acting as a Superman, you’re teaching your children to be supermen.”

Fritz Ottenheimer with the copy of CHUTZ-POW! featuring his story (photo Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh Facebook)

Some of the artwork depicting Fritz’s story in CHUTZ-POW! Volume 1

In the classroom, Walker and the Holocaust Center have developed CHUTZ-POW! to not only be used in a history class, but also in visual arts, language arts, journalism, and community engagement to complement the new holistic method of Holocaust education. The supplemental teacher’s resource guide provides examples of how the comic can be used to engage students in critical thinking. The Holocaust Center also uses CHUTZ-POW! as a bridge to introduce the audience to survivors more directly. After discussing the comic in class, the Holocaust Center can bring a local Pittsburgh survivor into the classroom or school. This completes the circle of knowledge and awareness for the student as the characters they’ve just read and discussed are brought to life in front of them as true superheroes.

It Begins at the Kitchen Table

In a perfect world, these successful examples of Holocaust education in 2021 would be universally mandated, funded, and applied systematically across the board. Students would enter society as ambassadors of a pro-social movement that, as Robert Putnam advocates, is destined to return but needs the innovative, problem-solving minds to foster it.

Nick Haberman’s experience has shown that the previous model of Holocaust education does not stay with students. Trauma doesn’t teach and they do not respond to assignments requiring reflections about torture or killing. What he has found is that success lies in stories of resilience (Haberman, 2021):

“Is it surprising that we have the most success in classrooms with stories of resilience in an era of trauma-informed learning? In an era where we’re talking more openly about mental health, we shouldn’t be surprised that the students get the most inspired by stories of people that went through hard times, and that recovered from those hard times, whether it’s because they were persecuted of their race or religion or their sexual preference or whatever identity it is, this theme of resilience is, I think, what makes them want to get involved in contemporary advocacy campaigns. This is LIGHT.”

Current Holocaust education classes such as Haberman’s do not focus on stories of the “Anne Franks” who perished. They read about rescuers and young resistance fighters who fought the Nazi regime and suffered for their cause by bringing attention to the indignities and atrocities. These stories inspire students decades later to stand up for what they believe in and show that even against the might of Nazi Germany and all their bystanders, young people can make a difference. Students today identify better with someone like Knud Dyby or Tina Strobos who were only a few years older than they are now and plotted and outwitted the Nazis. They are inspired by stories of hardship and all its twisting emotional anguish because, up until the end, whether they lived or died, they persevered. These themes are channeled into modern advocacy. Haberman adds,

“Since we have, sadly, millions of stories from the Holocaust to choose from, why not choose the ones that inspire.”

Another change in students’ perspective over the years is religion. The past decades have seen a trend in fewer young people participating in organized religion. Every year when Dr. Baird surveys her students, more and more identify as atheist. In terms of the Holocaust and rescuers, it is important for these students to learn that morality is not tied to religion. Both Strobos and Dyby came from families that eschewed the church, but in no way did it lessen or weaken their morals. Their heroism and bravery were built on the foundation of role models who respected life and people from different backgrounds. These role models today are the key to instilling lasting impressions regardless of whether they are formed in the church or not. It needs to begin in the sanctuary of the home. Rabbi Jeffry Myers from the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh summarized how students learn morals best (Bairnsfather et al., 2021):

“It begins at the kitchen table, so the real challenge is how do you get a seat at the kitchen table, which is where in the literal sense, parents are the primary educators of their children. Their children are going to learn morals, the customs, the family beliefs as they sit and have a meal together. In absence of the opportunities to sit and dine with the families who need to do that, it goes back to education. More and more in America we live in silos that were clustered by those who were so similar and alike to us without daring to build bridges to connect to the other silos, the danger is in what we see every single day because when you don’t know neighbors it leads to mistrust, misunderstanding, fear, loathing, eventually “the h-word” in speech and eventually to violence. So it has to start early on that we need to know all about our neighbors no matter what faith you are the maximum you’re going to be is 50% of the population of the world. So there is still half a planet that you don’t know anything about. I think when we learn more about our neighbors we can respect who they are, where they come from, their customs, the foods they eat, their family stories. When we have that kind of respect for other people, they’re no longer “others.” They are part of the family of humanity and they’re not “them” anymore, it’s all now part of “us.” So in absence of kitchen table, it has to come from education.”