Comparing 1968 and 2020 Civil Rights Events in the Media

Introduction

In the summer of 2020, our country has been feeling reverberations of change among the daily presence of uncertainty. It has not been just the anticipation of a heated presidential election or the unraveling control of the Coronavirus pandemic. The heat of summer has been intensified by the May 25th murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis by the hands of white police officers and captured on a bystander’s video. His death was the final straw in a succession of unarmed Black person deaths and racist actions in the span of a few months. The swift organization of the Black Lives Matter protest movement and episodes of rioting in the weeks after hasn’t been seen since the civil rights marches fifty years earlier.

In the spring of 1968, our country was also on the brink of change with protests against an unpopular war in the jungles of Vietnam, an upcoming presidential race, and civil rights demonstrations galvanized by the powerful yet non-violent leadership of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Cities like Pittsburgh were hotspots of civil unrest because of decades of segregation, inadequate education, and the lack of job opportunities. Ten years earlier, Pittsburgh’s most vibrant Black community, the Lower Hill District, was literally bulldozed by the city along with the promises of change that carried feelings of neglect into the 1960s. Attitudes and actions towards segregation and racism were no longer simmering, but boiling. When Dr. King was assassinated on Thursday, April 4th, the pot of boiling water was thrown against the wall by those who had been pushed too far. To the Black community, Dr. King’s death was “the death of hope.”[i]

How these two historic events were communicated to the public by the news media is worth examining. Mainstream newspapers owned and operated by white men portrayed the riots of April 1968 through a single lens focused on their most important advertising demographic: the white middle class. The Black press, however, led by voices that amplified these struggles, wrote far different stories that showed the well-worn chasm in American journalism. In 2020, most Americans and businesses like to think of themselves as progressive and inclusive, and in many ways, they are. However, the lack of diversity in American news media continues to be a problem that results in stories that aren’t told and an important population misrepresented. News journalists and their media are responsible if the public lacks awareness of their community, whether their neighbors down the street or on the hill across town.[ii] This paper will look at how these two civil rights movements were covered by the mainstream news media and by the Black press.

Importance of Community-Based Journalism

The earliest days of block-printed news in 15th century Europe brought together people of small villages and growing urban centers to share gossip and conversation over a drink at the public house or on a bench in the town square. Investigative journalism two centuries later began as a way to give the public information on its rulers rather than have it filtered by what the rulers wanted their citizens to know. The early days of investigative reporting not only ensured transparency in the government, but also explained the effects of their decisions on the public.[iii] As America urbanized in the 19th and 20th centuries, the press was also as a source of education to immigrants who came to America and Blacks who resettled in northern cities. The papers taught them how to be a good citizen and how to make informed decisions. Journalism had a challenge and an “obligation to provide members of the community not only with the knowledge and insights they need but with the forum within which to engage in building a community.”[iv] With the media’s new mid-20th century business model, however, being a source of information to these diverse communities was not seen as profitable.

Over the years, the community forum provided by the press and their independence to cover news has changed drastically. Today, it is influenced by advertising dollars, ratings, and targeted demographics rather than the good of the community. As newspapers budgets were cut, they chose to focus on stories in areas that would spend their money on higher end advertisers. The smaller businesses no longer had the budget to advertise in the paper so their customers in poorer, often Black communities, were left out. The papers streamlined their coverage to target more white, middle class areas, effectively removing news from the Black and poor neighborhoods[v] and brandishing them as outcasts of their own city. At that point, who does the news represent? Everyone becomes less informed as they only see themselves reflected in the stories, if at all, and the media shows bias.

Rather than being guided on what stories to cover by advertising or what editors behind a desk think the readers should know, journalists should go back to the streets, pounding the beat, getting to know its citizens and what is effecting their lives by asking questions about their day, their hopes and fears.[vi] This is echoed by long-time Pittsburgh journalist, Chris Moore, whose city editor mentor at the Pittsburgh Courier told him to go to the street to find the news and make your sources. One of the reasons the Courier could relate so well to the Black community was the editor’s own strategy of walking around talking to the judges, the club goers, and the “ladies of the nighttime sisterhood” who knew what was “breaking on the street.” Moore now tells young reporters, “Instead of waiting for an assignment from the news desk, make the news desk respond to you.”[vii]

Importance of Diversity in Journalism

One of the key reasons that different communities are not represented in the media is the lack of racial diversity in the newsroom itself. In 1967, the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders found that fewer than 5% of newsrooms employed Black reporters. In 2017, the American Society of News Editors’ annual study of newsroom diversity found that, while the American population was 40% minority, a typical newsroom employed only 16.5% minorities, and larger newsrooms staffed 23.4%.[viii] After five decades of supposed progress, this is a paltry improvement that reflects the difficulties minorities have obtaining degrees in journalism, getting a job in the newsroom, and feeling empowered to stay in that career.

The Columbia Journalism Review in 2015 published research on several important reasons that minorities were still not equally represented in the newsroom. It began at the university level, where minorities were only 21.4% of journalism or communications degree graduates. When looking for a job, only 49% found employment compared to 66% of white graduates. On further examination, the study found three important reasons for this inequality:

The minority students may attend a school that does not have the resources for a campus paper, or if they do, they feel “ostracized by a mostly white newsroom.”

Most minority students must work during school because of their financial position and cannot afford to take an unpaid internship, which are most common in the news field. White students tend to be more affluent and able to gain experience at these internships, which gives them firsthand experience that is desirable when looking for a job.

This lack of exposure to internships also removes minority students from networking possibilities and adds to the disadvantage of being hired in a full-time job.[ix]

In newsrooms that are already “homogenous” because of the established practice of hiring people with the same backgrounds and views, there is little reason for white newsroom managers to hire diverse staff or interns when their curated audience and advertisers are homogenous as well.[x] Tal Abbady on NPR summarized this broken system that continues to challenge people of color: “The thinking goes that people will just bubble up and navigate their way to where they need to be, which disputes the classic liberal notions of a meritocracy that prizes talent and perseverance. But you have to be seen, mentored, nurtured. The patriarchal message is that with enough luck and individual pluck, things will happen. But it takes real intention.”[xi]

This lack of diverse newsroom staff is directly related to the stories and messaging communicated to the public. Stories are left unreported or unbalanced. The media giant controls the views of the community by telling them what they should know based on their lens of the world, rather than reflecting the prism of a multi-cultural community. The mainstream objectivity comes off as a single mainstream mentality. However, when a story is reported through a Black reporter’s lens, it is expanded and shaped to where there may be “only one side, or numerous sides with various textures and shades.”[xii]

Another reason for newsroom leadership to diversify is because they have ingrained beliefs about the Black community and a distrust of their own reporters that are difficult attitudes to change. Moore shared a story from the 1960s when they were putting together stories to commemorate Dr. King. His white editor did not believe that Moore could factually know that Dr. King wanted to be known as “A drum major of justice” even though Moore was a Black reporter reporting on the Black community. It’s the same pattern that today’s young Black journalists experience. Fellow Pittsburgh journalist, Brentin Mock, recalled that his white editor held a long-standing view that the Black community is fundamentally homophobic. Mock had to go above and beyond to challenge the editor’s attitude to the point of having a heated argument in the office. It was not the first or last time he had to defend the Black community from “these cemented beliefs in the newsroom.”.[xiii] When minority staff need to defend their truths against the white establishment on a daily basis, the cumulative extra efforts are exhausting and take time and energy away from doing their actual job, which white reporters do no experience. At a recent online discussion with local Black Pittsburgh journalists, it was agreed that newsrooms must not only diversify their staff, but leadership opportunities must open up for minority staff. The Pittsburgh media (as well as corporate and government positions) are largely led by white men who ought to know when it’s time to step aside and offer opportunities to improve their communities and journalistic integrity under new leadership. Until that happens, nothing in the local media will improve.[xiv]

What will help the media to address the needs of their community is to diversify their own staff, not just with different ethnicities and backgrounds to meet diversity hiring requirements, but to improve the newsroom’s intellectual diversity. This concept breaks the traditional white, mainstream mentality and fertilizes it with rich viewpoints that can describe the array of cultural and societal experiences: racial, gender, ideological, social class, economic.[xv] The American melting pot still exists, and the modern newsroom needs to become that melting pot itself in order to report on Americans’ shared struggles and successes. This ideal newsroom doesn’t grow overnight, but can begin with intentionally seeking out young diverse minds and mentoring them and giving them an opportunity that might otherwise elude them.[xvi]

Background on the Black Press in the U.S.

The idea of diverse writing in the media and more prominent Black voices is not a progressive 21st century idea. In the 1700s, white-owned printing presses in America churned out stories about Blacks that still resonate with the racist tones seen today. Their stories stoked fear in their white audience with stories of slave rebellions, crimes, violence, and fear that rendered to keep the Black man in check and from gaining prominence in the new world. “Innuendo about slaves activity was sometimes all that was needed to produce a news story that created panic among the white population.”[xvii] But in 1827, nurtured by the oral tradition of songs and sermons that gave hope to the Black slaves, the dream of an independent Black publication was realized. The four printed pages of New York City’s Freedom’s Journal was the first Black newspaper in America and heralded the era of the Black press.[xviii] Every week its readers learned stories important to their community, such as religion, science, politics, children, fashions, crime, US and foreign news, speeches, and ship sailings.[xix] As their publication grew, the editors knew that their intended audience, especially in the South, was mostly illiterate, so they marketed the paper to educated ex-slaves and free Blacks who moved to the North and were seen as upwardly mobile.[xx] They also hoped that their unique stance would be read by progressive white people who were sympathetic to the Black cause.[xxi]

The Black press spread across the country, continuing to print articles of solidarity and inspiration throughout the Civil War and the end of slavery at the close of the 1800s. Their numbers are difficult for historians to pinpoint because archiving was not a principle concept, and many of the small papers did not last long. One estimate says that 1,200 papers began publication between 1866 and 1905. The Pittsburgh Courier, considered the most influential during its run, began in January 1910, with its circulation growing to 3,000 copies per week in a city with a population of 25,000 Blacks.[xxii] By 1930 the Courier’s efforts to enrich the Black person’s narrative grew to twenty pages and four regional editions, and was distributed in every state plus Europe, Cuba, Canada, the Philippines, the Virgin Islands, and the British West Indies. The Boston Post called the Courier “the best Black paper in the country” due to its excellent staff, writing, editorial cartoons, and national news coverage.[xxiii]

The United States’ involvement in World War II brought about great strides in the rights of Blacks directly due to the unabashed stories and editorials published in the Black press. The Pittsburgh Courier in particular challenged the U.S. government and military on their discrimination in the armed forces. The paper began the “Double V” campaign spurred by a letter from a reader who questioned why he should sacrifice his life for his country when he fought his own battle at home. The campaign became a rallying cry for the Black community that bolstered their confidence and notoriety. The Black press and the campaign influenced change for Black citizens, from enrollment in all the armed services to government and assembly line jobs for Black women. The Courier’s leadership boosted their circulation by 84% during the war, the greatest readership for any of the Black papers.[xxiv] The Black press was so influential and successful in the 1940s that a poll by the Chicago Defender found that 81% of Blacks in 1945 “did not make decisions on local and national matters until they saw what the Black press wrote about the issues, and 97% felt that the main reason that Blacks were obtaining equal rights and becoming first class citizens was that the Black newspapers had sounded a continual drumbeat against inequities.”[xxv]

The civil rights campaign gained legal momentum in 1954 with the U.S. Supreme Court declaring unanimously in the Brown v. Board of Education case that school segregation was unconstitutional.[xxvi] This decision paved the way for equality not only in public schools, but in any publicly operated facility. It also prompted Americans to finally begin viewing Blacks as equal stature.[xxvii] The next two decades were defined by significant events that furthered the civil rights cause such as the Montgomery bus boycott; the march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama; speeches and marches led by Dr. King; and legislation like the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968.[xxviii] As these events furthered a new era of equality in America, they also increased the integration of Blacks into mainstream, white newsrooms as the editors sought to hire talented Black reporters to cover the stories in the civil rights movement. Ironically the integration that Blacks so longed for also led to the eventual drop in circulation and long downward spiral of the dedicated Black press as their audience bought the mainstream newspapers to seek out those stories written by the best Black journalists.[xxix] The Pittsburgh Courier’s circulation dropped from an all-time high of 350,000 in 1945, to 186,000 in 1954.[xxx] Some Black periodicals changed their tactics in an attempt to retain their audience by adopting the appearance and wire stories of mainstream white papers, but it was not seen as a panacea. Other Black publishers claimed that trying to look more mainstream would erase their identity as “crusaders” and that they needed to remain “distinctively Black.”[xxxi]

As its circulation dropped to 25,000 in 1966, the Pittsburgh Courier was bought by the publisher of the Chicago Daily Defender and renamed the New Pittsburgh Courier. To many historians of the Black press it was considered the end of an era and that the paper never regained its talent for pushing the boundaries for racial justice.[xxxii] A few years later, it still found purpose filling a crucial hole for its readers.

Media Coverage of the 1968 Death of Martin Luther King, Jr.

To most of mainstream America, the spring of 1968 was about continued antiwar protests against the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War. For the civil rights movement, Memphis, Tennessee, was the site of another important event in March when its Black sanitation workers went on strike to protest unequal pay, and poor working and safety conditions that led to the deaths of two workers. Martin Luther King, Jr. arrived in Memphis to lend support, lead a peaceful march, and speak to over 15,000 supporters. A white supremacist, however, had been tracking him and assassinated Dr. King on Thursday, April 4, while he spoke from his hotel balcony.[xxxiii]

The news of his assassination that Thursday evening lit a match of unrest in cities around the country. Peaceful protests and violent riots with looting and fires occurred in over one hundred cities throughout the weekend.[xxxiv] Newspapers rushed to the scenes to report what they saw and learned. Leading papers like the New York Times and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette published apocalyptic headlines that dramatized the events and angled them towards what mainstream, white America had been conditioned to read. The headlines reinforced their belief on why their communities needed to be segregated – for their own safety from violent thugs and lower-class citizens. The New York Times headlines from the weekend after Dr. King’s assassination commonly used trigger words such as violence, looting, danger, riots, fear, death toll, anger, fires, and dead. Headlines stoked fear and depicted war zones:

“Thousands Leave Washington as Bands of Negroes Loot Stores,”[xxxv]

“D.C. Hotels Report Tourists Avoiding Capital Area,”[xxxvi]

“5,000 U.S Troops Sent as Chicago Riots Spread; Death Toll is 9 and 300 Are Hurt.”[xxxvii]

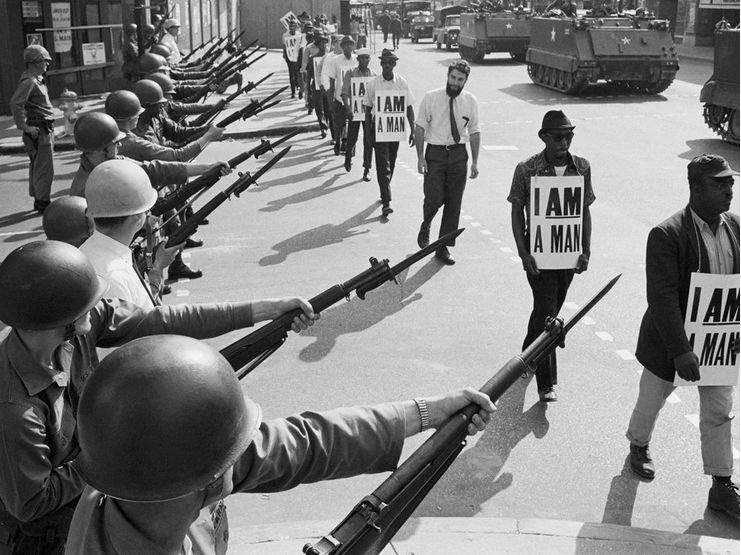

The photos showed whole city blocks on fire with the National Guard acting as sentinels in war zones; maps of the areas were like battle maps warning the white public not to go. The news articles were skewed towards violence and fear without background information or interviews on why the Black communities were protesting or rioting. One reporter on-scene in Chicago interviewed a Black sanitation worker who said, “I don’t know what’s the cause of it all.” A white business owner defending his store was dubbed a “wizened little white man” whose business had not been touched because he is well-liked in the community, and also had the aid of “three large Negro helpers.” The same reporter observed how “tense” it was for the National Guard to be working there, but provided no sense of how tense it was for those crying for change.[xxxviii]

In Pittsburgh that weekend, the Post-Gazette provided similar mainstream coverage, relying on Associated Press and New York Times news wire services while a few reporters ventured to the Hill District neighborhood that was the epicenter of unrest. As with the New York Times, the paper’s headlines depicted fear and a war zone:

“Negro leader shot at motel; violence erupts”[xxxix]

“Pittsburgh Hit By Gangs In Hill District”[xl]

“Guard, State Troopers Sent In To Quell Hill District Disorder, Refugee Centers Set”[xli]

Local articles were either memorials to Dr. King or depictions of violence with points of view taken from the police and National Guard, and how “weary” they were or interviewing a Port Authority spokesman about how the bus schedule will operate during the city’s curfew so that citizens will be able to get to and from work.[xlii] The reporting did not include interviews with Blacks about how weary they were or backstory of why the Hill District was burning.

The timing of Dr. King’s death was such that the New Pittsburgh Courier had just gone to press for the week and missed the opportunity to publish the news on Saturday, April 6. Their next edition was the following Saturday, April 13. When it hit the newsstands, the Courier made a clear proclamation that the heart of the Black nation had been struck. Their headline in large Black type read:

“A NATION MOURNS Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. 1929-1968”

and was placed above the paper’s nameplate so there was no question where the importance of this event lay.[xliii] The national edition was thick with news, opinion columns, and thought-leader pieces about what this historic event meant to the civil rights cause. Headlines did not stoke fear, but sadness, honesty, and alarm for the future:

“Future of America At Crossroads”

“An Assassin Walks Among All Black Men”

“He Carried the Cross of Christ”[xliv]

The Black press’ longtime reputation for unobjective, emotional writing was on full display. The riots and violence were seen as “wounds”[xlv] and the journalists investigated why they were there. The articles showed reactions from Black leaders and Democratic presidential nominee, Robert Kennedy and his wife, Ethel, who showed empathy to the cause while touring the destruction in Washington, D.C.. Another article interviewed 34-year-old musician, James Brown, who cancelled his shows to stem the violence in Harlem and provide a voice of calm leadership:

“It took us a long time to get a hero, now all these rioting and looting and burning, man that’s crazy. That just takes us back 100 years…The people got sense, but they will listen to me, because they know I’m straight and I mean it from my heart.”[xlvi]

One photo and caption of a Black child surrounded by Guardsmen captured the chaos’ effect on the innocent:

“Lost and unable to find her way in all the confusion of the rioting in Chicago last week, the little girl shown above breaks into tears as questioning National Guardsmen, looking like men from Mars in their gas masks, appear to frighten her more.”[xlvii]

Overall, the Black press coverage of King’s assassination and ensuing events were a completely different style and perspective from mainstream papers. The articles humanized the events, investigating the root causes and effects on the Black community. It wasn’t about the physical violence; it was about the decades and centuries of emotional toll. They were interspersed with editorials about peace and who could fill the shoes of a leader like Dr. King, and interviews with presidential aides who discussed President Johnson and Congress would be working to improve unemployment, education, job opportunity programs, housing assistance, and the other elements that led to civil unrest. The Courier chided white readers with unfettered directness why the riots happened:

“Whitey has always tried to determine what Black folks think and why they do things. His problem is that he just won’t accept the fact that he doesn’t understand. He has been anti-Black oriented all his life and now in a crisis he becomes an expert having only investigated the situation from the surface. The ghetto is a smoldering not of frustration, bitterness and poverty. There is no one reason for what happened last week. It’s the result of years and years of anguish….Who says Black folks are to blame at all? But if we are, it’s because we were forced into it. Whitey has always concerned himself with the results and not the causes. What prompted last week’s disturbance? Ask Whitey to search his conscious for the answer.”[xlviii]

Media Coverage of the 2020 Death of George Floyd

The sentiment in the Black community was similar in summer of 2020 with the death of George Floyd on Memorial Day. The video of Floyd’s brutal arrest as he was pinned to the street under the knee of white policemen and the pleas for his life were unescapable. Riots and protests began immediately in Minneapolis then around the country. Social media, especially Twitter, was quick to circulate video, photos, and near real-time accounts of Black Lives Matter protests from Minneapolis and cities around the country. The news media quickly sent staff to cover the events around the country and leveraged these social media accounts to feed the 24-hour news cycle.

Overall, the 2020 newspaper and website coverage and tone of George Floyd’s death and subsequent protests and riots was far different than in 1968. As much as our society still needs to progress to end racism, the coverage of this story was less racist in the mainstream media. Reviews of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and New York Times showed more empathy to why Black Americans were protesting and the need to end police brutality. Each mainstream paper interviewed Black people, albeit briefly at times, to hear their thoughts on the long backstory of why this happened. There were no headlines injecting fear of the “angry Negro” or descriptions of violence reminiscent of a hostile enemy on American soil. The tone from the New York Times to the Des Moines Register was one of empathy and identifying the reasons for the protests and anger. Unlike in 1968, the reality captured on live video by thousands of citizens was impossible to spin: Black and white people of all social influence protesting together, moms and dads, children, looters and agitators, peaceful protesters, and aggressive police and those who raised a fist. The photos in particular captured the new diversity of mixed races combined in anger and sense of purpose to end police brutality and gain strides that their parents and grandparents couldn’t fifty years ago. While the Pittsburgh Courier’s Teenie Harris worked from dawn into the night in the 1960s capturing emotional photos and developing film by hand that gave his viewers unique views of the Hill District and Black communities during the riots, the country in 2020 had tens of thousands of photographers capturing their real-time experience to tell the collective Black Lives Matter story.

In the weeks after George Floyd’s death, the New Pittsburgh Courier published daily articles, commentaries, and editorials on its website that weighed heavily on the Black American’s perspective and anger for where their country remains. However, like many small papers, the Courier has a staff and circulation a fraction of what it was before so its depth of coverage was far less than in 1968 or compared to a mainstream mogul like the New York Times. Only a few pages of the digital edition were dedicated to Floyd and the Black Lives Matters protests. Their energy did produce a special report that covered three full pages on their digital edition that focused on the impact on Pittsburgh Black families’ lives and fears, which was insight of local families not found elsewhere. The other big local story important to the Black community was the removal of two Black reporters from the Post-Gazette and potential bias by the Post-Gazette’s leadership. Several commentaries, such as from Jesse Jackson, Sr., discussed the need for police reform, on-going white supremacy, and reflection on where the community is now.[xlix]

The Post-Gazette did interview Blacks and white allies at protests for quick perspectives, but in-depth dedicated coverage, such as the impacts on lives in the Hill District community, were scarce. The Post-Gazette had daily local and national coverage of the protests and interviews with local government, police, and Black leadership about the city’s position on what was happening. But a week after George Floyd’s death as protests in Pittsburgh had filled city streets for days, the Post-Gazette was also embroiled with its own public relations problem and division within its staff and newspaper guild. Two Black reporters had been removed from covering the city’s protests when Post-Gazette leadership claimed they showed bias in a Tweet sent May 31 that would prevent them from being objective.[l] The removal was condemned by the Newspaper Guild of Pittsburgh, the Pittsburgh Black Media Federation, and other reporters at the Post-Gazette. The story made national headlines and now is under a lawsuit. The Pittsburgh City Paper, which wrote a series of articles following the controversy, released a 2016 photo of Post-Gazette editor Keith Burris posing with then-presidential candidate Donald Trump. Its article questioned the editor and his paper’s own hypocrisy and journalistic bias.[li] Could this internal and external strife have affected how the events were covered by western Pennsylvania’s largest newspaper?

The New York Times, with their far-reaching resources, had extensive coverage of protests around the country, ranging from dedicated interviews into the reasons for the protests, gripping on-scene video montages and photos capturing a range of raw emotion. Their headlines were not sensational or fear mongering. They presented the seriousness of the situation without making it one race against the other. Their words were careful to say “angry demonstrators” rather than racial descriptions like “negros” or “Blacks” rioting and protesting. They emphasized the “treatment” of George Floyd which identified the problem for the protests, interviewed Black Minneapolis locals, asked protesters what they wanted (“Justice, but we have to have some patience.”), and added extensive backstory not only about the previous deaths Black people by whites in recent months, but also the longtime racism that white people do not see. Two months after Floyd’s death, the Times’ daily coverage of the 2020 racial movement is ongoing as it evolves to include police reform, battles with federal agents planted in cities, and removing racist memorials and business names.[lii]

Conclusion

There is optimism that certain mainstream press outlets in 2020 have shown such leaps in changing their racist tones of reporting on the Black community and their fight for equality. However, this paper only superficially examined two mainstream newspapers and was not a thorough analysis that could make a final conclusion on the evolution of attitudes in reporting racial injustice protests by the mainstream press. The recent Race, Protest, and Media seminar with local Black journalists like Chris Moore and Brentin Mock revealed there is still much to overcome. With digital technology becoming more easily produced and accessible to the public, our media stream now abounds with independent news websites and podcasts that fill a void for voices not included in mainstream media. Perhaps there is similarity between this digital era and the rush of hundreds of Black newspapers produced in the late 1800s. The question, like then, is, “Who will survive to be heard and lead their community?”

“A newspaper that fails to reflect its community deeply will not succeed, but a newspaper that does not challenge its community’s values and preconceptions will lose respect for failing to provide the honesty and leadership that newspapers are expected to offer.”[liii]

Endnotes

[i] “Pittsburgh residents recall the state of the city following Dr. King’s assassination in 1968,” New Pittsburgh Courier, accessed July 26, 2020, https://newpittsburghcourier.com/2018/04/05/pittsburgh-residents-recall-the-state-of-the-city-following-dr-kings-assassination-in-1968/

[ii] Bill Kovach, Tom Rosenstiel. Elements of Journalism (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2014), 246.

[iii] Kovach, Elements of Journalism, 171.

[iv] Kovach, Elements of Journalism, 209.

[v] Kovach, Elements of Journalism, 244.

[vi] Kovach, Elements of Journalism, 257.

[vii] “Race, Protest and Media,” Zoom seminar, July 16, 2020.

[viii] “Why the Black press is more relevant than ever,” CNN, accessed July 26, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2017/11/30/opinions/newsroom-diversity-mainstream-media-opinion-love/index.html

[ix] “Why aren’t there more minority journalists?” Columbia Journalism Review, accessed July 26, 2020, https://www.cjr.org/analysis/minority_journalists_newsrooms.php

[x] Kovach, Elements of Journalism, 282.

[xi] “The modern newsroom is stuck behind the gender and color line,” National Public Radio, accessed July 26, 2020, https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2017/05/01/492982066/the-modern-newsroom-is-stuck-behind-the-gender-and-color-line

[xii] CNN.

[xiii] Race, Protest and Media.

[xiv] Race, Protest and Media.

[xv] Kovach, Elements of Journalism, 282.

[xvi] NPR.

[xvii] Patrick Washburn, The African American Newspaper, Voice of Freedom (Northwestern University Press, 2006), 13.

[xviii] Washburn, The African American Newspaper, Voice of Freedom, 11.

[xix] Washburn, The African American Newspaper, Voice of Freedom, 22.

[xx] Washburn, The African American Newspaper, Voice of Freedom, 23.

[xxi] Washburn, The African American Newspaper, Voice of Freedom, 22.

[xxii] Washburn, The African American Newspaper, Voice of Freedom, 129.

[xxiii] Washburn, The African American Newspaper, Voice of Freedom, 133.

[xxiv] Washburn, The African American Newspaper, Voice of Freedom, 4.

[xxv] Washburn, The African American Newspaper, Voice of Freedom, 181.

[xxvi] Washburn, The African American Newspaper, Voice of Freedom, 197.

[xxvii] Washburn, The African American Newspaper, Voice of Freedom, 198.

[xxviii] “Brown v. Board of Education,” History.com, accessed July 26, 2020, https://www.history.com/topics/Black-history/brown-v-board-of-education-of-topeka

[xxix] Washburn, The African American Newspaper, Voice of Freedom, 199.

[xxx] Washburn, The African American Newspaper, Voice of Freedom, 185.

[xxxi] Washburn, The African American Newspaper, Voice of Freedom, 200.

[xxxii] Washburn, The African American Newspaper, Voice of Freedom, 5.

[xxxiii] “The strike that brought MLK to Memphis,” Smithsonian Magazine, accessed July 26, 2020, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/revisiting-sanitation-workers-strike-180967512/

[xxxiv] “King Assassination Riots,” Wikipedia, accessed 7/26/2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/King_assassination_riots

[xxxv] “Thousands leave Washington as Bands of Negroes Loot Stores,” New York Times, accessed July 26, 2020, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1968/04/06/issue.html

[xxxvi] “D.C. Hotels Report Tourists Avoiding The Capital Area,” New York Times, accessed July 26, 2020, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1968/04/07/issue.html

[xxxvii] “5,000 U.S. Troops Sent as Chicago Riots Spread; Death Toll Is 9 and 300 Are Hurt,” New York Times, accessed July 26, 2020, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1968/04/07/issue.html

[xxxviii] “28 Chicago Blocks, a Strip of Shops, Bear Riot Scars,” New York Times, accessed July 26, 2020, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1968/04/07/issue.html

[xxxix] Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, accessed July 26, 2020, https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=gL9scSG3K_gC

[xl] Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, accessed July 26, 2020, https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=gL9scSG3K_gC

[xli] Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, accessed July 26, 2020, https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=gL9scSG3K_gC

[xlii] Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, accessed July 26, 2020, https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=gL9scSG3K_gC

[xliii] New Pittsburgh Courier, accessed July 26, 2020, https://search-proquest-com.authenticate.library.duq.edu/hnppittsburghcourier/docview/202553952/pageviewPDF/ABE3B78DCC3C43B2PQ/1?accountid=10610

[xliv] Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, accessed July 26, 2020, https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=gL9scSG3K_gC

[xlv] Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, accessed July 26, 2020, https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=gL9scSG3K_gC

[xlvi] New Pittsburgh Courier, accessed July 26, 2020, https://search-proquest-com.authenticate.library.duq.edu/hnppittsburghcourier/docview/202553952/pageviewPDF/ABE3B78DCC3C43B2PQ/1?accountid=10610

[xlvii] New Pittsburgh Courier, accessed July 26, 2020, https://search-proquest-com.authenticate.library.duq.edu/hnppittsburghcourier/docview/202553952/pageviewPDF/ABE3B78DCC3C43B2PQ/1?accountid=10610

[xlviii] “Did Dr. King’s Assassination Cause Riots?” New Pittsburgh Courier, accessed July 26, 2020, https://search-proquest-com.authenticate.library.duq.edu/hnppittsburghcourier/docview/202551613/pageviewPDF/8DD90AB1BE194948PQ/4?accountid=10610

[xlix] New Pittsburgh Courier, accessed July 26, 2020, https://issuu.com/michronicle/docs/npcourier6.10.20

[l] “Pittsburgh Post-Gazette removes a Black reporter from George Floyd protest coverage says union,” Pittsburgh City Paper, accessed July 26, 2020, https://www.pghcitypaper.com/pittsburgh/pittsburgh-post-gazette-removes-a-Black-reporter-from-george-floyd-protest-coverage-says-union/Content?oid=17403485

[li] “Pittsburgh Post-Gazette editor’s photo with Trump proves own journalistic bias he claims to condemn,” Pittsburgh City Paper, accessed July 26, 2020, https://www.pghcitypaper.com/pittsburgh/pittsburgh-post-gazette-editors-photo-with-trump-proves-own-journalistic-bias-he-claims-to-condemn/Content?oid=17439564

[lii] “Race and America,” New York Times, accessed July 26, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/news-event/george-floyd-protests-minneapolis-new-york-los-angeles?action=click&pgtype=Article&state=default&module=styln-george-floyd®ion=TOP_BANNER&context=storylines_menu

[liii] Kovach, Elements of Journalism, 209.

Alternative and Independent Black Media Websites

1. Atlanta Black Star, https://atlantaBlackstar.com/

2. Blavity, https://blavity.com/

3. Bloomberg City Lab, https://www.bloomberg.com/citylab

4. NewsOne, https://newsone.com/

5. NPR Code Switch, https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/

6. Pittsburgh Current, https://www.pittsburghcurrent.com/

7. The Grio, https://thegrio.com/

8. The Skanner, https://www.theskanner.com/

9. The Root, https://www.theroot.com/

10. The Undefeated, https://theundefeated.com/